Geology factors into many units of the National Park System, but there are some parks that rise above all others if you have an interest in the geologic past...and present. What follows is a short list of some of the most geologically fascinating parks in the system, though we're sure you can add others.

In fact, we're so sure you'll cite others, that we intentionally crafted the headline to say "Ten Top Geologic Parks," and not the "Ten Best Geologic Parks." With that said, let's take a look at what's out there.

Arches National Park has more stone arches, windows, and bridges than anywhere else on Earth/Kurt Repanshek

Arches National Park, Utah

It's a fact: There is nowhere else on Earth where you can find in one location so many rock arches, bridges, and windows. Whether you hike out to Delicate Arch, stand before Landscape Arch, or frame yourself in one of the 'windows' or perhaps Turret Arch, spend any time in this park and you'll gain a new perspective for geology. The park's rock-itecture -- windows cut from stone, spindly arches longer than a football field, thin fins of rock -- and desertscape are otherworldly.

Arches holds the record for most nature-carved sandstone arches, with more than 2,000. Cut from the same geologic cloth as its neighbor, Canyonlands National Park, Arches' geology tells tales of long ago, when inland seas inundated this part of North America.

Badlands National Park is an intriguing landscape of geologic contrasts/Kurt Repanshek

Badlands National Park, South Dakota

Eerily eroded "badlands" -- what other word would you use to describe these naked hills? -- are front and center in this national park, evidence of the harsh environment and the poor soils. But there's more geology to the Badlands than just its namesake hills. You have the "Yellow Mounds," slight mounds colored yellow by the severely weathered soils.

"The Badlands were formed by the geologic forces of deposition and erosion," the Park Service points out. "Deposition of sediments began 69 million years ago when an ancient sea stretched across what is now the Great Plains. After the sea retreated, successive land environments, including rivers and flood plains, continued to deposit sediments."

No matter what season you find yourself in Bryce Canyon, you'll be amazed by the geology/Kurt Repanshek

Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah

Whimsical as the hoodoos that stand in phalanxes in the park's amphitheaters are, they also are towering examples of geology. Not quite 36,000 acres in size -- little more than a tenth the size of Canyonlands -- the drawing card of Bryce is its namesake amphitheater crowded with hoodoos and goblins that erosion has sculpted from the pink underbelly of the Paunsaugunt Plateau. Whether you gaze down upon the amphitheater, or stroll through it, the features known as Thor's Hammer, Queen's Garden, Natural Bridge, ET, Indian Princess, and the Warrior, just to name a few, fire your imagination and cause you to marvel at nature's artistic side.

If you can afford more time in the park and enjoy backpacking, the Under-the-Rim Trail is a great adventure, one that takes you away from the bulk of the park's visitors and gives you a view of Bryce's colorful underbelly. Striding along this 23-mile-long route takes you through a quiet, breathtaking wilderness of orangish geology and towering trees in which details elude those in a hurry

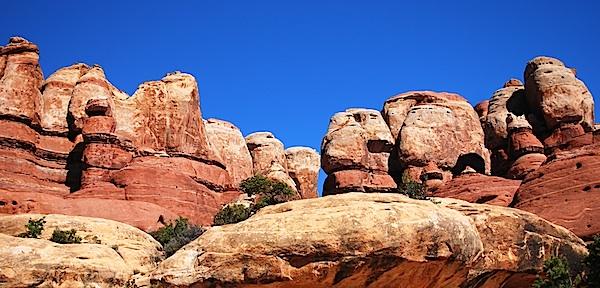

Hiking through Canyonlands gives you a pretty good idea of what Fred, Barney, Wilma, and Betty saw everyday/Kurt Repanshek

Canyonlands National Park, Utah

Fossilized sand dunes, old seabeds turned to sedimentary stone, and canyons cut by the Green and Colorado rivers all point to the mesmerizing geology of the Colorado Plateau. And all those features can be found within the boundaries of Canyonlands.

Baked by time like some multi-layer geologic tort, Canyonlands features a landscape cut by canyons, rumpled by upthrusts, dimpled by grabens, and even pockmarked, some believe, by ancient asteroids. A kaleidoscope of tilted and carved geology laid down over the eons -- red and white Cedar Mesa sandstone, the grayish-green Morrison Formation, pinkish Entrada sandstone, tawny Navajo sandstone, just to name a few of the layers -- help make Canyonlands the most rugged national park in the Southwest, and quite possibly if you find yourself deep in the Maze, in the entire Lower 48.

Canyonlands is a showcase of geology. In each of the districts, you can see the remarkable effects of millions of years of erosion on a landscape of sedimentary rock.

Travelers to Crater Lake National Park get to experience at least two volcanic craters -- the big one, and the one that forms Wizard Island/Kurt Repanshek

Crater Lake National Park, Oregon

Though a shimmering blue lake is the main draw to this park in southern Oregon, you can't ignore the fact that the lake fills a volcanic crater. Take the boat tour out to Wizard Island, get out to stretch your legs, and you'll find yourself on another crater -- the cinder cone that created the island. Back on the tour boat, you'll continue to circumnavigate the lake, and head past the Phantom Ship, a volcanic 'neck,' or vent turned to stone.

The big crater was formed almost 8,000 years ago when prehistoric Mount Mazama erupted over a handful of days. The outpouring of magma emptied a chamber below the summit of the mountain enough so that the summit collapsed inwards to form the crater.

Whether partially obscured by snow, or blazing under a cloudless sky, Grand Canyon National Park is a geologic encyclopedia/Rebecca Latson

Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona

Hike down to the Colorado River via the South Kaibab or North Kaibab trails in the park and you'll walk a geologic timeline.

"The Grand Canyon's excellent display of layered rock is invaluable in unraveling the region's geologic history. Extensive carving of the plateaus allows for the detailed study of the Earth's movements. Processes of stream erosion and vulcanism are also easily seen and studied," notes the National Park Service. "Nearly 40 identified rock layers form the Grand Canyon's walls. They have attracted students of earth history since 1858. Because most layers are exposed through the Canyon's 277-mile length, they afford the opportunity for detailed studies of environmental changes from place to place (within a layer) in the geologic past."

Though it can look a lot like Yellowstone National Park, Lassen Volcanic National Park has some fascinating geologic aspects/Kurt Repanshek

Lassen Volcanic National Park, California

With Lassen Peak, a dormant volcano almost always in view during your visit, geology is a prime topic at this park in northern California. Climb the peak and you can actually stand in its crater. Tour the Devastated Area and you'll see the aftermath, and renewal, of the area most impacted by the peak's 1914 eruption. Hike down to Bumpass Hell, and you'll come to understand a bit more about geology and volcanism.

It took an explosive event -- several, actually -- that brought Lassen Volcanic National Park into the National Park System. Eruptions in 1914 and 1915, well-documented by Benjamin F. Loomis, spurred Congress to establish the park in 1916. Loomis was on hand for the 1914 and 1915 eruptions (interestingly, major eruptions occurred in May of both years) to capture the blasts on film. Located near the southern tip of the Cascade Range, the national park also is found on the 'Ring of Fire,' a seismic zone that rings the Pacific Ocean. This 'ring' includes such notable volcanoes as Mount Shasta, Crater Lake, Mount St. Helens, Mount Rainier, ... and those that built the Hawaiian islands.

Yellowstone Natinonal Park corners the world market on geothermal exaltations/Kurt Repanshek

Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming

This landscape in Wyoming's northwestern corner holds the world's greatest collection of geothermal displays, with more than 10,000 geysers, hot springs, mudpots and fumaroles. Within Yellowstone's borders are vast lakes, raging rivers, and mountains seemingly made out of glass. What created this intriguing and varied landscape? Fire and ice. Fire in the form of molten rock that today fuels the park's geothermal basement, and ice in the form of incredibly thick and massive glaciers that once covered the region.

Driving Yellowstone's thermal features is a hot spot in the Earth's crust. Here in the park crust is so thin that heat generated by the Earth's molten core reaches the surface. Almost 17 million years ago, the plume of hot and partly molten rock known as the "Yellowstone hotspot" first erupted near what is now the Oregon-Idaho-Nevada border. As North America drifted slowly southwest over the hotspot, there were more than 140 gargantuan caldera eruptions ' the largest kind of eruption known on Earth ' along a northeast-trending path that is now Idaho's Snake River Plain.

The hotspot reached Yellowstone about 2 million years ago, yielding three huge caldera eruptions about 2 million, 1.3 million and 642,000 years ago. Two of the eruptions blanketed half of North America with volcanic ash, producing 2,500 times and 1,000 times more ash, respectively, than the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens in Washington state, university researchers say. Smaller eruptions occurred at Yellowstone in between the big blasts and as recently as 70,000 years ago.

Granite domes are one fascinating side to Yosemite National Park's geologic personality/Kurt Repanshek

Yosemite National Park, California

You can't stand in the Yosemite Valley and look at Half Dome and towering El Capitan and not wonder about geology. But don't stop there. Head out to Glacier Point and look down on the valley that glaciers and erosion created, or head down the Tioga Road and look at the granite domes time has formed.

Yosemite is a glaciated landscape, and the scenery that resulted from the interaction of the glaciers and the underlying rocks was the basis for its preservation as a national park. Iconic landmarks such as Yosemite Valley, Hetch Hetchy, Yosemite Falls, Vernal and Nevada Falls, Bridalveil Fall, Half Dome, the Clark Range, and the Cathedral Range are known throughout the world by the photographs of countless photographers, both amateur and professional. Landforms that are the result of glaciation include U-shaped canyons, jagged peaks, rounded domes, waterfalls, and moraines. Glacially-polished granite is further evidence of glaciation, and is common in Yosemite National Park.

Bighorn sheep, and humans, are draw to the curious Checkerboard Mesa in Zion National Park/Kurt Repanshek

Zion National Park, Utah

Walk the Zion Narrows and you quickly come to understand what a 'slot canyon' is. Trying to imagine how long it took the Virgin River to carve that slot through some 2,000 feet of sandstone is another thing. Look around Zion Canyon as you drive through it, at the three Patriarchs, at Angels Landing, at TK, and you'll really begin to appreciate geologic time and how very, very long it took to carve these features out of the landscape.

Geologists have traced 250 million years of history in the park's rock ramparts, and frozen in them is a fascinating fossil record. Exit, or enter, the park through its east entrance and as you cross Checkerboard Mesa the cross-etched sandstone is another lesson in geology.

Most of the sedimentation that went into Zion's geologic basement occurred during the age of dinosaurs (Mesozoic), while the uplift began in the Cenozoic, long after the sedimentary formations were laid down. The park is located along the edge of a region known as the Colorado Plateau. The rock layers have been uplifted, tilted, and eroded, forming a feature called the Grand Staircase, a series of colorful cliffs stretching between Bryce Canyon and the Grand Canyon. The bottom layer of rock at Bryce Canyon is the top layer at Zion, and the bottom layer at Zion is the top layer at the Grand Canyon.

Comments

Big Bend NP should have been on the list for geology plus it is a great wildlife park.I would rank it ahead of Badlands, Bryce, Crater Lake and Lassen Volcanic for variety of geologic features and varied scenery. Plus it has more variety in both plant and animal life than all of them.

Perhaps Acadia doesn't have the grand geological scale as the western parks. But Bubble Rock and other evidence in the first national park east of the Mississippi helped 19th century scientist Louis Agassiz conclude it was glaciers that moved huge boulders around, not floods of biblical proportions, as had been previously thought.

Maybe Carlsbad Caverns and Mammoth Cave in the top twelve.