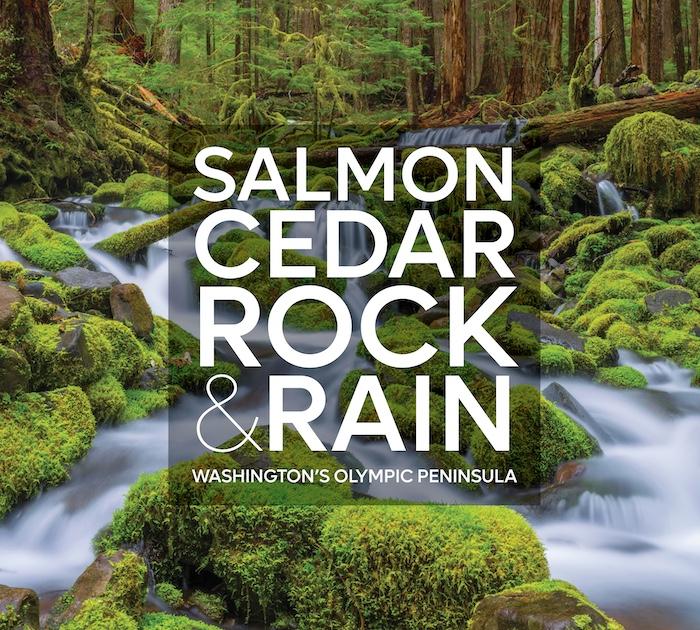

A rain forest setting in Olympic National Park/John Gussman

Review | Salmon, Cedar, Rock & Rain

By Kurt Repanshek

Bruised by a past of logging and dam building, the Olympic Peninsula of Washington state has demonstated its resilience time and again, and while climate change likely will inflict more bruises on the peninsula and its national park, Tim McNulty is confident it will endure.

"The genetic endurance of the peninsula, which goes back through the 2 million years of the Ice Age, has seen us through some pretty remarkable and catastrophic change," said McNulty, author of a new book on the rich and diverse ecosystems on the peninsula west of Seattle. "And that's kind of true for most of the Northwest forests, which experienced volcanic eruptions, glacial advances, epic fire episodes. These forests, these ecosystems, are resilient, and here on the Olympic Peninsula, because of the park, because of the wild areas of the [Olympic] national forest, a good part of that ecosystem was preserved, which I think is going to be extremely important in helping helping us through the coming changes."

The Olympic Peninsula is a wild and wooly place, even now in the 21st century. That’s no doubt largely because the heart of the peninsula is taken up by Olympic National Park, a more than 900,000-acre jigsaw puzzle of glaciers, peaks, rain forests, rivers, and Pacific coastline.

You could view the national park as three parks in one: The long, narrow coastal area pounded by the Pacific Ocean, the dense inland rain forests that cloak the Hoh, Quinault, and Sol Duc areas, and the high, craggy landscape that cups nearly 200 glaciers. The title of McNulty's book, a collaborative effort that blends his narrative with Indigenous voices and amazing photography, views the region in four parts: Salmon, Cedar, Rock & Rain, Washington's Olympic Peninsula.

The book [$32.95] from Braided River could be seen as a supplement to Olympic National Park, A Natural History, which McNulty first published in 1996 and which now is in its fourth edition. His latest project stems from a discussion he and others had some years ago about the need to bring Indigenous voices into the discussion around the peninsula's natural history, which also would be captured by a number of photographers.

"That became kind of the operating the operating principle for a newer book that would go beyond Olympic National Park [and] talk about the entire peninsula, the tribes, the different agencies doing different kinds of work on the peninsula, as well as the Park Service, Forest Service, wilderness areas, rivers and so forth," the writer explained during an interview for the Traveler's weekly podcast. "I felt that this one would be a complement to the natural history, which is in its fourth edition now, and would also be a little bit easier and prettier way to get into appreciating the peninsula, perhaps appeal to a more a wider and more diverse audience."

Running more than 200 pages, the hardcover book need not be read immediately from cover to cover, but savored in sections as time allows. The photography alone encourages time spent with it. You'll find the requisite images of waterfalls and storm-battered coastline and emerald rain forest, as well as shots of Coho salmon migrating up the Sol Duc River, a cougar cornered in a tree, comparisons of Anderson Glacier in 1936 and, in 2015, the lake created by the melted river of ice, and an underwater shot of a red-hued giant Pacific octopus.

McNulty's narrative, and the supporting essays, open windows and perspectives into the peninsula's ecosystems. There are essays from Indigenous writers that explore healing places long used by the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, the connections the Makah Tribe has with the rivers and the salmon that swim them, and how the S'Klallam Tribe got its name.

Giant octopus, Olympic Peninsula/Brandon Cole

"Much of my writing and some of the other writers who write about the park, our focus is the nonhuman community. And in my natural history [book], you may recall that there was a couple of chapters of human history. One was the conservation history, and another was just kind of a rough introduction to the diversity of tribal people who have lived on the peninsula since time immemorial. I think we all felt that that was an important part of the story here. They were the original stewards of this land," McNulty explained when asked why those perspectives were brought into the book. "The tribes continue to protect resources, work toward restoration, and in some instances, are very, very, very large parts of the community in the community that I live."

"...The tribes have been really leading the way toward the major [salmon] habitat restoration underway on the peninsula and throughout the Pacific Northwest today," he said,

As for the resiliency of the peninsula, McNulty points to its long history of coping with change. There were times over the past two million years when ice ages locked the peninsula and effectively turned it into an island and trapped, if you want to think of it that way, the resident flora and fauna. "Many species which were just cut off from their families continue to survive on the Olympics. Many became endemic species," he said. "I think there's a total of about 28 plants and animals and fish and amphibians that occur in the Olympics and nowhere else. The most popular of course, being the Olympic Marmot, who is kind of the hero of the high country. But there are also other small mammals and as I mentioned, fish and amphibians and plants."

Indigenous voices are brought into the book/Larry Workman

How the landscapes endure or change through ongoing climate change remains to be seen, but loss of glaciers and snowfield would impact down-mountain rivers, creeks, and streams, as well as the forests and species they nourish. Against the unknown changes and impacts, habitat restoration is seen as one tool to protect species going forward. As an example, since millions of dollars were spent to remove the Glines Canyon and Elwha dams work has been ongoing to restore the salmon fisheries in the Elwha River and elsewhere on the peninsula.

"The different agencies, primarily the tribes, also the State Department of Fish and Wildlife, are trying to work with restoring the natural functions of rivers so that they could provide the best possible salmon habitat they can facing this unknown of what's going to happen with a lesser snowpack," said McNulty. "Restoring ecosystems, restoring watershed ecosystems to the best point possible so that they may be in their best condition to deal with to provide habitat to encourage the survival of salmon in the face of reducing snowpack is the main effort underway now.

"...I do have faith that the ecosystem will make it in some in some form," he said. "I think the important work we do now is to try to, as Aldo Leopold said, make sure all the cogs and wheels are still here. Return extirpated species, like the wolf. Get rid of invasive species that were damaging the ecosystem, like the mountain goats, and do all we can to restore ecological process and healthy habitats."

Traveler postscript: Catch the Traveler's entire conversation with Tim McNulty in podcast Episode 244. Also, to learn more about the book and McNulty's collaborators, and to purchase a copy, visit this site.

The wild Olympic Peninsula of Washington state/John Gussman

Add comment