Holgate Glacier at Kenai Fjords National Park has been advancing in recent years/NPS

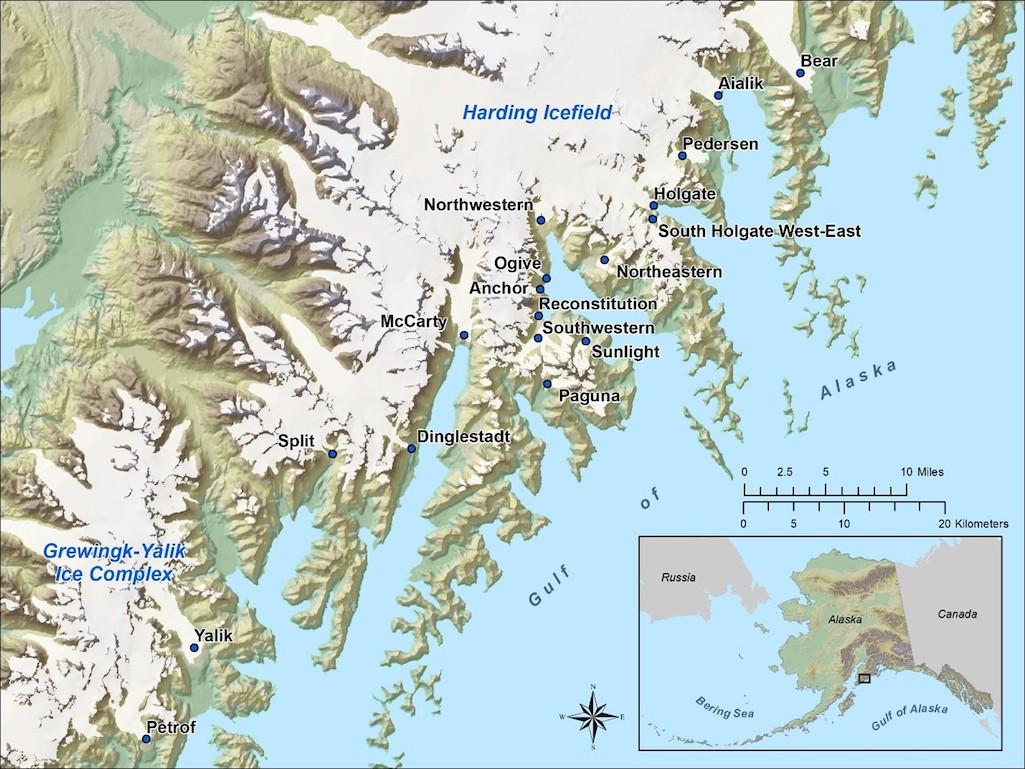

Nearly four decades of Landsat imagery have allowed researchers to closely monitor the retreat, and advance, of some of Kenai Fjords National Park's glaciers. The study didn't pinpoint the exact cause of the glaciers' movements, though, but documented for the National Park Service the behavior of 19 glaciers in the park located about two hours southwest of Anchorage, Alaska.

What the researchers, Deborah Kurtz from the National Park Service and Taryn Black, who recently received her doctorate in Earth and Space Sciences at the University of Washington, found was that since 1984 13 of the glaciers showed substantial retreat, four were relatively stable, and two had advanced over the decades. Their findings were published in early August in the Journal of Glaciology.

"We did not look at weather information for these glaciers. We were focused on just characterizing how much the glaciers have advanced or retreated over this time period," Black said during a Zoom interview with the Traveler. "But the data that we collected can be a really useful baseline for future researchers who might want to go into more detail on how different climate factors like temperature and precipitation were specifically affecting these glaciers."

Kenai Fjords was an obvious choice for their research. Across the roof of the park at an elevation of up to 3,525 feet stretches the Harding Icefield, which feeds more than three dozen glaciers. Covering 700 square miles, the icefield sends these rivers of ice off in all directions, some extending down through fjords to the Gulf of Alaska and so are called "tidewater" glaciers, while others terminate on land or in lakes. Hardy park visitors can hike up to the icefield, via a 4.1-mile trail (8.2 miles roundtrip) up from the Exit Glacier area.

The Holgate Glacier, which empties into the Gulf of Alaska, was one of the two that has been advancing in recent years, growing by about a third-of-a-mile, which came as somewhat of a surprise. Black said the glacier was thought to be in retreat because of a mound of sediment at its snout.

"When people saw that shoal (of dirt), they thought, 'Oh, the glacier has retreated, and it's starting to show land beneath it.' But it turns out," she continued, "that the glacier was actually building out this shoal in front of it as it advanced."

Kurtz, Kenai Fjords' director of interpretation and education, in an email said that the "Holgate Glacier’s advancing behavior has been previously observed in other tidewater glaciers and is described as one of the four stages of a tidewater glacier cycle. This cycle is influenced by local geography (such as fjord shape) in addition to climate. During this advancing stage, a tidewater glacier builds a sediment shoal which helps to reduce the rate of calving (ice loss at the terminus) and acts as a buffer from warm, marine waters."

But Holgate clearly is an outlier. Among the glaciers in retreat is Bear Glacier, which has lost about three miles of ice since 1984, when it was about 16.5 miles long. Pedersen Glacier has lost about two miles of ice since 1984 and currently measures about six miles in length.

Black said the two glaciers "tend to retreat pretty consistently year to year. Some of the glaciers were quite a bit more variable. But those lake terminating glaciers, so Bear, Pettersen and then Yalik Glacier, which is down at the southwestern end of the park, they are lake-terminating glaciers and for whatever reason, all three of those tended to retreat pretty consistently year to year."

The 19 glaciers included in the study are shown as blue dots. While Alaska glaciers are just a small fraction of the planet’s glacial ice, they are losing ice faster than any other glacierized region outside of Antarctica and Greenland/NPS, Deborah Kurtz

The other glacier that has been advancing is the Paguna Glacier, which pushed forward about a tenth of a mile from 1984 until about 2007. Since then it has been relatively stationary, the researchers found. A likely contributor to the glacier's advance, said Black, was that the river of ice had gained a layer of insulation from a 1964 earthquake that shook Alaska and sent a landslide across Paguna.

"That thick cover of rock debris on the glacier actually insulates the glacier surface. So it's thick enough to insulate the glacier and that allows it to advance a little bit because it's not melting as much as it would otherwise," she said.

As these and other glaciers retreat, the loss of ice can have a dramatic impact on the landscape.

"The retreat of these glaciers impacts the surrounding vegetation and wildlife, most apparently because land cover is absolute, so the loss of ice equates to the gain of a different landcover and different habitat," said Kurtz. "For example, when a tidewater glacier retreats, the area that was previously occupied by ice is inundated by marine water, expanding the length of the sea-filled fjord. In Kenai Fjords, this is exemplified by Northwestern Glacier.

"Typically, when terrestrial glaciers retreat they expose bare rock, which is then vegetated in a described sequence of vegetation succession, providing different terrestrial habitats throughout the process," she continued. "This is evident at most locations in our study, such as the fjord walls in McCarty Glacier and the valley in front of Northeastern Glacier. Glacial retreat also leads to the development and expansion of rivers and lakes, creating new or additional freshwater habitats, such as at Pedersen and Bear glaciers. Further research is needed to describe and quantify these new landcover and habitats developing in the wake of ice melt, which may result in both positive and negative effects. For example, glacier retreat can uncover new land for plants to colonize, but it can also affect the balance of nutrients and sediments in aquatic environments and reduce habitat availability for animals like harbor seals that use glacier environments. Additional studies in Kenai Fjords are seeking to better understand the impacts of glacier retreat on the marine environment."

The changes, Black said, can happen sooner than many might imagine.

"I think people often think of glaciers as something that changed very slowly. I mean, we have the term 'a glacial pace' that means something that's changing incredibly slowly," she said. "But glaciers are actually incredibly dynamic. And there can be really rapid changes, especially, with these tidewater glaciers, like the ones at Glacier Bay National Park, or these glaciers that I looked at in Greenland. Some of the glaciers at Kenai Fjords, like I mentioned earlier, climate is an important factor in how these glaciers are changing. But there's additional factors that come into play with these tidewater glaciers, like the shape of the fjord that they're sitting in and things like that that can really accentuate how dynamic they are and how quickly they change."

In their study, Kurtz and Black said glacial retreat at Kenai Fjords National Park "will likely impact tourism, as many people come to the Kenai Fjords to see calving tidewater glaciers and the abundant marine wildlife that thrive in the current conditions."

"The Kenai Fjords viewscape is changing dramatically as tidewater glaciers retreat onto land and land-terminating glaciers retreat into the alpine or out of sight around a bend," they added.

Traveler postscript: Listen to the Traveler's interview with Taryn Black in National Parks Traveler Episode 187: Kenai Fjords' Glaciers.

Add comment