The crystalline McDonald Creek in Glacier National Park. / NPS, Tim Rains

Mapping Glacier’s Wildest Places

A new storytelling tool helps both park managers and visitors understand the value of park wilderness.

By Kim O’Connell

Along McDonald Creek in Glacier National Park, a scenic, tree-lined portal into the park’s interior, the water creates an ever-evolving symphony of sound. In some spots it gurgles and hisses; in others, it roars and rushes. Sometimes, it makes almost no sound at all.

Preserving the ability to hear natural sounds like this—not the engines of cars and buses, the generators of concession stands, or the thwap-thwap-thwap of sightseeing helicopters taking off and landing—is part of the reason for officially designated wilderness areas. At Glacier, a new GIS-based “story map” is giving park managers a sophisticated tool for understanding the wilderness character in various parts of the park, while offering park visitors another way to know the park’s wildest areas, too.

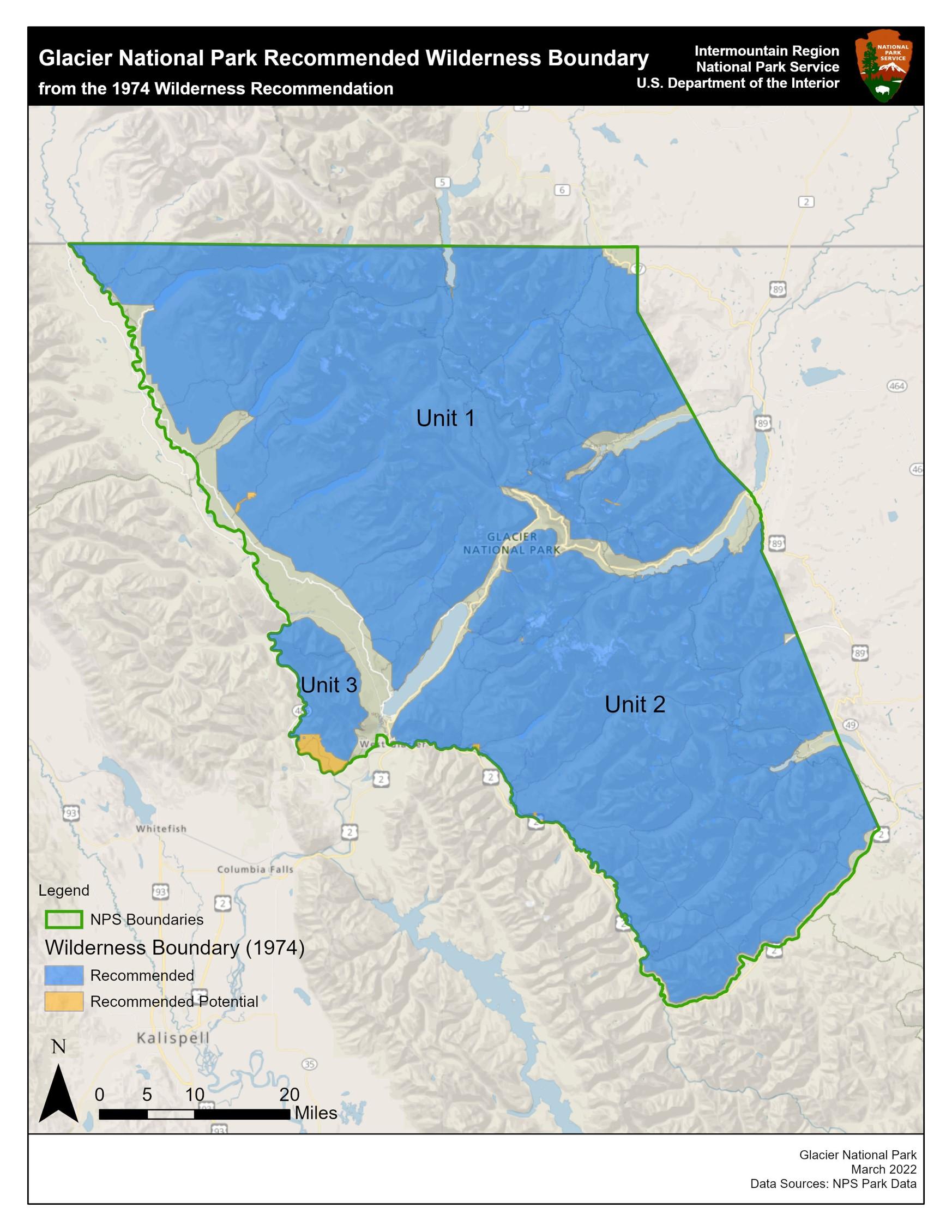

What sets Glacier apart in the world of official wilderness, however, is that none of the park is actually designated wilderness. In 1974, park staff produced a wilderness study and environmental impact statement on the park’s roadless areas, a process that included public input. The resulting recommendation to Congress proposed to designate three units of the park, comprising 927,550 acres (about 92 percent of the park’s area), as formal wilderness. But Congress never followed through and so the proposal was never codified into law. Yet, because the area had been recommended as potential wilderness, for the past five decades it’s been managed as such in accordance with National Park Service policy.

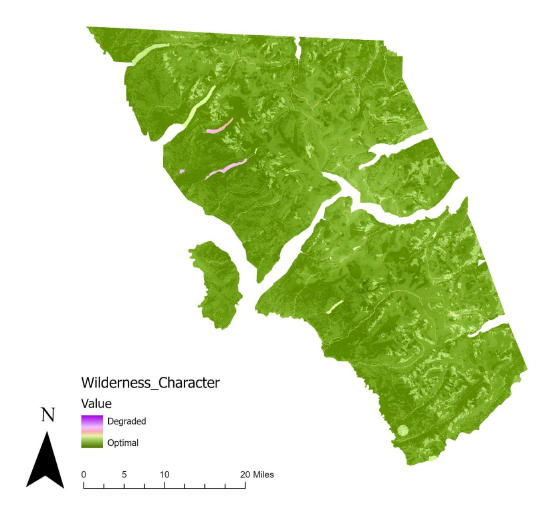

This comprehensive map illustrates the wilderness character in various areas of the park. Although much of the park retains significant wilderness values, there are areas of noticeable degradation. / NPS image

“The Wilderness Act was passed in 1964 and is one of the cornerstones of land preservation in the world, and definitely for the United States, it's the highest form of land preservation that we have,” says Brad Blickhan, Glacier’s wilderness and wild & scenic river coordinator and a 35-year veteran of the park. “I went to some wilderness training in 2013 and I had this epiphany that, because Glacier is not designated wilderness, and that recommendation was from 1974 and has never been enacted upon, we were not bringing it to the forefront like we could. I realized there was so much we could bring out about wilderness that’s falling off the radar.”

Currently, 111 million acres of federal land, including many areas managed by NPS, have been designated as wilderness. These are exceptional natural areas that are managed in such a way that preserves their untrammeled quality. People are allowed to visit and enjoy wilderness areas, but may not make any permanent or destructive developments, such as structures, or use motorized vehicles and mechanical devices.

In the face of pervasive and growing threats to the national parks, including climate change, invasive species, and overcrowding, the Park Service recognizes the importance of assessing park features—both natural and cultural—and monitoring change over time. Scientists at Glacier have collected data about the park for years, but they lacked a cohesive and standardized way to analyze the data, represent it visually, and communicate it to park managers and the public.

That’s where the story mapping comes in. About 10 years ago, scientists at the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute in Montana and the Wildland Research Institute in the United Kingdom developed an approach to mapping threats to wilderness character using geographic information systems (GIS), a spatial data system that is used in all kinds of mapping and data analysis applications. The Leopold Institute published the first wilderness character story map for Death Valley National Park in 2012 and has since produced similar maps for Olympic, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, Black Canyon of the Gunnison, Gates of the Arctic, Denali, and Saguaro national parks. The scientists also created a set of technical guidelines to help lead other parks in the process of creating a wilderness story map. Glacier is the first park to do so independently of the institute.

Jillian McKenna, Glacier’s wilderness GIS coordinator, took the lead on developing the story map, working in concert with Blickhan. The public-facing story map is accessible via a visually dynamic scrolling website that includes explanations of what wilderness is and the five categories by which wilderness character is assessed: its untrammeled quality, natural quality, undeveloped quality, primitive recreation quality (solitude), and other features such as cultural resources.

With visitation to the park booming, as it is throughout the park system, it’s important for visitors to understand these qualities and why they matter, McKenna says. (Visitation to Glacier has been around 3 million annually since 2016, not counting the lockdown year of 2020.)

As this map illustrates, more than 90% of the park is managed as wilderness. / NPS image

“By getting a better understanding of what wilderness is, visitors can help protect wilderness character,” she says. “If they know there are these areas that are threatened because there's so many people, they'll think about whether or not they're going to walk off trail and go on that social trail and kill all that vegetation. By doing little things, the public can help.”

To raise money to retain McKenna and develop the map, the park turned to the Glacier National Park Conservancy, the park’s friends group. Wild Tribute, the national parks apparel company, also donated funds for this work through its 4 The Parks campaign, in which they donate 4 percent of their proceeds to park projects around the country.

“The park had this database that had really become outdated and just not functional anymore, with handwritten notes and things like that,” says Lacy Kowalski, the conservancy’s associate director of programs and policy. “Jillian's really taken on making this a functional database, and we've invested in tablets for the rangers to take out to the field so they can do standardized data collection and bring that back and just plug it into the database.”

So far, the data has revealed that much of the park retains a significant degree of wilderness character, but certain areas are demonstrably degraded. Changing temperatures, changing hydrology, longer fire seasons, invasive species, and direct human impacts are all likely to cause even more degradation going forward. But park staff are hoping that by standardizing data collection and having a robust tool with which to analyze and visualize the data, park managers can do all they can to protect the park’s most vital features.

“Wilderness monitoring and wilderness character mapping are just very important tools for us to set up this baseline for what this park is going to look like, for my kid or my kids’ kids, in the future,” Blickhan says. “In land management throughout the country we're not doing a very good job of educating the American public about the stuff they actually own and the laws we've passed to preserve places like Glacier….So it's all part of just laying the foundation for showing the public what we have and figuring out how we can use all the information to identify threats and protect wilderness for the future.”

Add comment