Sure, the National Park Service could just call August 25th its birthday, but the term 'Founder's Day' seems more fitting since the Park Service was the brainchild of a great many people who contributed to its inception.

From the vision of early conservationists and naturalists such as John Muir and Gifford Pinchot and the formation of the Service and its early years with Stephen Mather, Horace Albright and Arno Cammerer, to the massive strengthening of park infrastructures through the assistance of the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s, the birth and growth of the Park Service can be compared to the ancient trees of Sequoia and Redwood national parks.

The national park idea was the sapling which took hold with deep and complex roots which grew tall and strong through the years.

The Park Service has evolved tremendously since the early days of the Service, when many parks didn't even have access roads or any functioning visitor use facilities. But who were the so-called founders? Many people are familiar with the names of the early directors of the Service, but there were many others who helped the service evolve into what it is today, and are not as widely known.

Here are some of their stories:

Harry Yount

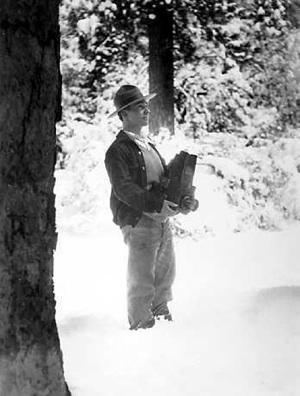

Harry Yount in 1873, Interior Department photo.

After the war, Yount traveled West and worked for the Army, transporting supplies between forts along the Bozeman Trail. Having gained a reputation as an experienced hunter, Yount was hired by the Smithsonian Institution in 1872 to collect specimens of animals for taxidermy display, many of which were exhibited during the Centennial Exposition of 1876.

In 1880, he was employed as a seasonal guide for early mapping expeditions of the Rocky Mountains by the Department of the Interior, and was eventually appointed as the first Gamekeeper of Yellowstone National Park. One of his first reports stated that protection of the park could not be accomplished by just one man, and urged the formation of a ranger force, therefore being heralded as the first national park ranger and for setting the standard for protection of wildlife in national parks.

Dr. Horace J. McFarland.

Horace J. McFarland was born in 1859, in McAlisterville, Pennsylvania, the son of Civil War Colonel George McFarland. At age 12 and after only four years of formal education, McFarland went to work in his father's printing shop in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. His father later opened Riverside Nurseries alongside the Susquehanna River, which inspired in his son a love of plants and outdoor beauty.

Dr. Horace J. McFarland, via Capital Preservation Committee, state of Pennsylvania.

McFarland opened his own printing company at age 19, and soon became the country's premiere publisher of horticultural catalogs through his groundbreaking work with color photographs. He went on to pen dozens of gardening books, several of which are still renowned in horticultural circles. In 1891, McFarland became dedicated to improving the city of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Working with architect Warren Manning, McFarland developed a plan to build parks, new sewage systems, and filtered water to the city, bringing about dramatic improvements to Pennsylvania's state capital.

In 1904, McFarland was elected president of the American Civic Association, an organization dedicated to improving the natural landscape of cities nationwide, a position he would hold for 20 years. He used his influence with the Roosevelt administration to protect Niagara Falls from hydroelectric plants, and became a driving force behind the creation of the NPS with other noted conservationists such as Stephen Mather, Horace Albright, Robert Marshall, Robert Sterling Yard, California Congressmen John Raker and William Kent, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., and Richard Watrous. They planned the formation of the NPS and strategized on how to protect the parks.

McFarland made it his life's work to educate the public and bring about civic improvements in cities across the country.

Lt. Col. Charles Young

In 1903, Young was appointed acting superintendent of Sequoia National Park, thus becoming the first African-American superintendent in the history of the Park Service.

Lt. Col. Charles Young, Library of Congress photo.

Although Sequoia had been authorized 13 years before, the park was still highly undeveloped and difficult to visit. The Army had been charged with building an access road to the Giant Forest, home of the world's largest trees, but in three summers, only five miles of road had been built.

When Young and his troops arrived, they set to work and completed more in one summer than had previously been completed in three years. The roads that Young and his troops built, having since been improved, are still in use today, and millions of visitors have benefitted from the hard work and dedication of Young and his troops.

Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane

Conservationists such as John Muir were opposed to many of his ideas. Indeed, Lane advocated for the damming of the Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite, a move that created a reservoir that currently serves 2.4 million Californians in San Francisco, San Mateo, and Alameda counties, as well as some communities in the San Joaquin Valley. It also generates electricity for the city of San Francisco. (Today there are ongoing efforts to see the reservoir drained.)

Lane was responsible for enlisting Stephen Mather to be the Service's first director, along with advocating for the construction of the Alaska Railroad.

Frederic Law Olmsted, Jr.

Born in 1870, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. was the son of Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., known as the father of American landscape architecture.

Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., Library of Congress photo.

He joined his father's firm in 1891, and his first contributions were to two notable projects: the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago and the world famous Biltmore Estate in North Carolina.

After his graduation from Harvard University and his father's retirement, Olmsted and his brother John took over management of the firm, and spent the next several decades working on thousands of landscape projects nationwide, including Central Park, the National Mall, the grounds of the White House and Cornell University. In 1899 he became a founding member of the American Society of Landscape Architects and served two terms as its president. The following year he was appointed instructor in landscape architecture at Harvard, where he helped create the country's first university course in the profession.

In 1901, Olmsted was appointed to the MacMillan Commission by President Theodore Roosevelt, charged with updating and implementing Pierre L'Enfant's century-old plans for Washington, DC. By 1910, Olmsted was approached by the American Civic Association for advice on the formation of the NPS, and was responsible for key language in the legislation.

For the next 30 years, he advised the NPS on issues of management and the conservation of water and natural resources. His work at Acadia, Everglades, and Yosemite national parks, along with countless others has left an indelible mark on the NPS and on the park system as a whole.

Olmsted was also responsible for a guide to the selection and acquisition of land for the California park system that became a model for other states in the future. Olmsted spent the remainder of his years working to save the historic Redwoods on the California coast, and Olmsted Grove was dedicated to him in 1953 at Redwood National Park for all he accomplished to protect America's national parks.

George Melendez Wright

George Melendez Wright was born in 1904 to a wealthy San Francisco family, his father a sea captain and his mother a member of a prominent El Salvadorian family.

George Melendez Wright, NPS Historic Photo Collection.

Both his parents died when he was very young, and Wright was sent to live with his aunt, Cordelia Ward Wright, who later adopted him. Wright spent his youth hiking and birding in the Bay area, and showed a keen interest in natural history.

He spent two summers as an instructor at a camp for Boy Scouts during his teenage years, and was president of the Audubon Club at his high school before attending the University of California at Berkeley. He graduated in 1925 with a degree in forestry and began working as a field assistant to one of his professors.

Throughout his time at Yosemite, Wright became increasingly concerned about the wildlife within the park. Poaching, uncontrolled populations of elk and deer, along with the tameness of natural predators such as black bears, caused Wright to conceive a plan to deal with his concerns. He proposed that there be a wildlife survey office and wildlife biology plan for the NPS.

The fledgling NPS could not justify such an expenditure at that time, and since Wright was independently wealthy, he assumed all costs for the undertaking, including staff salaries and expenses. He continued to fund wildlife conservation efforts for the NPS until the program's value could be proven. Wright's findings were published in 1932 and 1933 in the series Fauna of the National Parks of the United States, and established the basis for wildlife conservation in American national parks.

Wright was tragically killed in an automobile accident in 1936 after concluding a survey at the newly authorized Big Bend National Park. He was only 31 years old when he died, but his contributions to wildlife conservation in national parks continue to resonate today.

These men and many others contributed to the formation of the NPS, and have helped the Service grow into what it is today. But their contributions go far beyond the formation of the NPS. If not for the work of Wright, Olmsted, McFarland, Young, Lane and Yount, our America would be a very different place. For this we must be grateful and make the most of the amazing places these men worked so hard to preserve, protect and build.

Add comment